Even a newspaper man, if you entice him into a cemetery at midnight, will believe in phantoms, for every one is a visionary, if you scratch him deep enough. But the Celt is a visionary without the scratching. -- W. B. Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888)Rooted in so many different European traditions, it's curious to think that Hallowe'en may be the holiday that best embodies the persistence of our culture. All Europeans observe some version of this celebration of night and the unconscious; and we do so with a remarkable consistency. The distinctions between England's Bonfire Night and our Hallowe'en are so superficial that common and abiding origins can be discerned almost "without the scratching". Our society may be altered beyond all recognition (not to mention endurance), but we still want our children to experience the kind of Hallowe'en we knew.

Hallowe'en is not an official holiday. No one gets the day off work. Yet, year after year, we just go ahead and celebrate anyway. Year after year, allegations of devil-worship and Satanic ritual are quietly ignored. And in a day when so many of our holidays are in retreat, Hallowe'en prospers. What accounts for this decidedly un-Canadian determination to see that it does?

In prehistoric Europe, these crucial few days (October 31 to November 2) were redolent with beginnings and endings.

By now, the crops were meant to be in, animals would have been brought down from distant pasture, and thanks given for this bounty. Here, past, present and future met to mark, not just the end of summer, but the advent of the Celtic New Year. As with many archaic societies, the Celts' day began at dusk; their year likewise commenced as darkness gathered. While Samhain (Sah-win) -- literally "the day between years" -- incorporated aspects of our Thanksgiving, their feast was more profound, a kind of cornucopia of infinite dimension. Samhain was the occasion to honour the ancients and celebrate that most primordial of mysteries -- the conclusion of the growth cycle and the implicit promise of renewal and rebirth encoded therein. Admirers of Eastern philosophy will be disappointed to know that the Celts celebrated the opposing aspects of darkness/light, night/day, cold/warmth, death/lifelong before the concept of yin and yang was patiently explained to Western dummies.

At this time, when distinctions between life and death were obscured, supernatural forces were presumed to extend to the world inhabited by men. At Samhain, souls of the recently deceased set out for their journey to the otherworld. With the veil between the worlds now so thin and permeable, the spirits of departed kinsmen were thought to seek out the warmth and comfort of good cheer as the time for their leave-taking approached. These were not the ghoulish undead of our Hallowe'en fantasies, but enlightened spirit guides and guardians of the wisdom of the tribe. People made offerings of animals, fruits, vegetables -- and fire. Fire was sacred to the Celts and their great bonfires were meant to aid and light the souls on their way (and possibly, to keep them at bay). It was a time of heightened spirituality, of divination, and of fear. It was a dangerous time for men, when ghosts, fairies, and demons might be abroad.

This Celtic inheritance is of enormous significance to North Americans because, whether or not we realize it, most of us have Celtic blood running through our veins. At its height during the 3rd century B.C., the Celtic World was enormous, ranging from southern Spain to the Caucausus from the North Sea to the Mediterranean. That great, untamed empire of individualists was unconquered and ununified by any external force (save culture) from its appearance in the 8th century B.C. until the advent of Christianity. Most of us are vaguely aware that the early Christian church accomodated the old pagan traditions of Yule (Christmas), Ostara (Easter), and Samhain or Hallowe'en (All Hallows Eve), but this was hardly the remarkable concession we moderns might imagine. In a world dominated by natural rhythms, the waxing and waning of sun and moon would tend to dictate division of the year the world over. Indeed, this season was sacred to the ancient Egyptians (worship of Isis), Native Americans (dances), and the Indo-European Hindus (Diwali or New Year).

In A.D. 601 Pope Gregory I issued an edict to his missionaries, instructing them to refrain from destroying local objects of worship, and consecrate them to Christ instead. This tolerance was to be short lived. The church came to realize that the mere act of sprinkling a little holy water on pagan rites was insufficient to "rehabilitate" them. It wasn't long before the people's experiences with the old beliefs were condemned as evidence of witchcraft and the old gods came to serve as a template for Satan (a wholly Christian concept). In 1248, Pope Innocent IV founded The Holy Office, better known to us as The Inquisition. By 1484, Pope Innocent VII had appointed Heinrich Kramer and Jakob Sprenger as inquisitors. Their Malleus Maleficarum described in exquisite detail, the tortures that might be employed to obtain a confession of witchcraft.

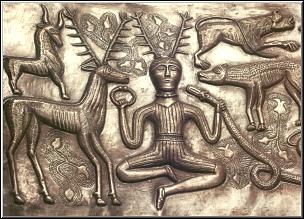

Christianity transformed Cernunnos, the horned god of the male aspect, of virility, and protector of woodland animals, into the embodiment of evil, the incubus, Satan. [Image: Cernunnos, surrounded by cult-animals, with a torque (neck-ring) in one hand and a ram-headed serpent (representing virility) in the other. From the Gundestrup Cauldron, c. 100 BC. Cernunnos, the oldest of the Celtic deities, may be a later incarnation of the horned god of palaeolithic cave art.]

Christianity transformed Cernunnos, the horned god of the male aspect, of virility, and protector of woodland animals, into the embodiment of evil, the incubus, Satan. [Image: Cernunnos, surrounded by cult-animals, with a torque (neck-ring) in one hand and a ram-headed serpent (representing virility) in the other. From the Gundestrup Cauldron, c. 100 BC. Cernunnos, the oldest of the Celtic deities, may be a later incarnation of the horned god of palaeolithic cave art.]

The rudiments of our Hallowe'en festivities probably hearken back to our most remote origins: certainly, the donning of costumes, the ritual giving of food, and the preeminence of fire are all elements that would have been familiar to our European ancestors. However, their very persistence over the many intervening centuries indicates that Hallowe'en observances may serve some more vital psychic need.

"Celtic society, like all early societies, was highly structured and organized, everyone knew their place. But to allow that order to be psychologically comfortable, the Celts knew that there had to be a time when order and structure were abolished, when chaos could reign. And Samhain, was such a time. Time was abolished for the three days of this festival and people did crazy things, men dressed as women and women as men. Farmer's gates were unhinged and left in ditches, people's horses were moved to different fields, and children would go knock on neighbours' doors for food and treats in a way that we still find today." -- Philip Carr-Gomm, Elements of the Druid Tradition

Samhain's visceral appeal remains immediate enough to keep today's experts arguing about the nature of the feast. Some modern Christians insist that observances were bloodthirsty (abductions, human sacrifices, a blob of human fat sputtering cosily in a lantern).

Modern pagans dismiss this as nonsense, asserting that the feast was profoundly religious, providing an occasion to honour ancestors -- not to increase their numbers. Curiously, both factions are prepared to agree that natural law would have been suspended for the duration. On the eve of Samhain, every home allowed the hearth fire to burn out, whether this was to make the house an unappealingly cold target for ghosts, or to facilitate a ritual relighting of the fires from a sacred source on New Year's Day depends upon your understanding of the holiday's purpose. Resisting subsequent cultural overlays and prohibitions, the most essential features of the old Druidic rites survive to this day. Ironically, even within the church itself, where costumes or vestments are donned, food is ritually given and candles lit to commemorate the souls of the dead.

When the Romans conquered Britain, they brought with them their November 1st festival honouring Pomona, goddess of fruiting trees. This accorded with existing Celtic ideas about the worthy apple. The growth cycle of the apple was reckoned such a miraculous thing that Avalon, (that Western land where spirits of the dead dwelled) was distinguished by an abundance of apple trees bearing fruit year round. Divination games with apples were important at Samhain; it was said that the first to "get a bite" bobbing for apples would marry in the coming year. Even good Christian children today recite the alphabet as they twist the stem from an apple to discover the first letter of their beloved's name.

Supernatural properties were historically ascribed to the jack-o'-lantern as well. There is a poisonous yellowish-orange mushroom called Jack-o'-Lantern that appears to "glow" in the dark. Jack-o'-lantern was another name for will-o'-the-wisp, fox fire or corpse candle. Called marsh gas by unromantic scientific types, this small flame moving through the darkness must have terrified the ancients. Thus, putting a Jack-o'-lantern in a window to frighten off fairies and other troublemakers was already an old practice when the world was young.

Not surprisingly, the most agreeable origin story comes from an Irish folk tale. "Jack" was an incorrigible drunkard and practical jokester who managed to trick Satan into climbing a tree. Once Old Nick was up, Jack carved a cross in the trunk and trapped him there. Then, Jack pressed his advantage (and his luck) to dictate the terms of a deal; if the devil would promise to never tempt him again, Jack might just be persuaded to let him down. Poor Jack. His misdeeds caught up with him right enough when he died. Barred from heaven as a drunken lout, he was equally well-remembered by the devil, who refused him the sanctuary even of hell. When Satan was kind enough to fling a burning ember at the impudent sod, Jack scooped it up for a makeshift turnip lantern. There goes Jack, doomed to wander the cold, dark ways of the netherworld through eternity. Here's living proof that you can't bargain with the devil (though it may be useful to know that there are turnips in hell). When the ideally suited New World pumpkin made its debut, the rusticated turnip was retired.

In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III decreed that All Saints' Day should be "moved" from May 13th. The day devoted to all the hallowed ones, "All Hallows" or "All Saints" Day, was now November 1, and the day following that (November 2), "Hallow Tide" or "All Souls" Day was set aside to honour those who had not been saints. Thus, the evening preceeding all this -- (October 31) -- was "All Hallow E'en". "Here we can see most clearly the way in which Christianity built on the pagan foundations it found rooted in these [British] isles. Not only does the purpose of the festival match with the earlier one, but even the unusual length of the festival is the same." Philip Carr-Gomm, Elements of the Druid Tradition.

The tradition of going from house to house wassailing, (caroling in exchange for a reward at each door) was a tradition associated with all the major Celtic festivals, although the "treat" would likely have been of the liquid variety. "Begging" food goes back to mummers and guisers, but really came into its own with the practice of "souling" during the 9th century. On All Souls Day, beggars (and later children) went from house to house in search of "soul cakes" (a lump of bannock bread baked with currants). The donor's pious charity guaranteed the recipient's prayers to speed the souls of dead relations heavenward from purgatory. A similar practice survives today under the Eastern Orthodox rite. On Crete, for example, each family prepares a tureen of boiled wheat "berries", pomegranate seed, raisins, currants and almonds which is carried through the village. At each house, a little is portioned out and a little of that householder's added to the mix. By the end of the day, each villager brings home a (theoretically) identical mixture to honour all the departed.

There is nothing intrinsically evil about Hallowe'en. The celebration we know today is equal parts Celtic pagan and Mediaeval Christian prayer ritual. So successfully have they blended that where the one leaves off and the other begins is now impossible to discern. Hallowe'en ought to be that happy circumstance where the Christian overlay complements older practices, but the one seems to be eternally damned at the eternal expense of the other. The annual Hallowe'en squabble guarantees that another feast utterly unique to us is hobbled, thanks to our imperfect understanding of our own heritage. It's especially galling that those who would treat a gaggle of candy-munching miniature ghouls and ballerinas like devil worshippers are the very people who most deplore the loss of that other sacred pagan/Christian tradition -- Christmas.

Unfortunately, this is all as predictable as a flea-tormented dog snapping at its own tail.

What can we expect when every one of our traditions either "excludes" or "exploits" somebody, hurts somebody else's feelings, or (the worst sin of all) keeps OUR culture viable and fertile. Are fundamentalists NOT offended when uncostumed little new Canadians come calling at their door for the free candy? It's a growing trend, and one that casts an entirely new, bittersweet light on the phrase "trick or treat".

For pagan and Christian alike, this was a time of remembering and reverence for those who came before us. However, since it seems to need emphasis, it was also an opportunity for people who lived short, hard lives to look to their full larder, to laugh at the devil and tweak his nose. It was supposed to be fun.

The great secret about Hallowe'en is this: the very act of remembering the dead means that you are not yet numbered among them. That ought to be irreverent enough for anyone.

No comments:

Post a Comment