Hellenic (Greek) spies at Sardis watched the rumor of invasion assemble into reality as the Persians, battle gear and all, headed West. The newly formed pan-Hellenic council -- knowing of the advancing onslaught, but not knowing exactly where to place the Hellenic forces -- opted to give King Leonidas of Sparta a 7,000 strong pan-Hellenic army of Thebans, Thespians, Athenians, and Spartans to protect the narrow mountain pass laying north at Thermopylae. (The Hellenic council chose instead to concentrate their forces south in the isthmus awaiting a naval invasion.) The pan-Hellenic army of brothers put aside their petty differences (they were plagued by incessant internecine wars for years) and unified under the banner of Greece. Little did they know their fate would go down into history as one of the greatest and most honorable defenses of Western Civilization.

Hellenic (Greek) spies at Sardis watched the rumor of invasion assemble into reality as the Persians, battle gear and all, headed West. The newly formed pan-Hellenic council -- knowing of the advancing onslaught, but not knowing exactly where to place the Hellenic forces -- opted to give King Leonidas of Sparta a 7,000 strong pan-Hellenic army of Thebans, Thespians, Athenians, and Spartans to protect the narrow mountain pass laying north at Thermopylae. (The Hellenic council chose instead to concentrate their forces south in the isthmus awaiting a naval invasion.) The pan-Hellenic army of brothers put aside their petty differences (they were plagued by incessant internecine wars for years) and unified under the banner of Greece. Little did they know their fate would go down into history as one of the greatest and most honorable defenses of Western Civilization.

As Xerxes' army approached, the Hellenes got word of their location, and prepared for the coming darkness. The Hellenes gathered at an old wall built by the Thessalians before them, which served to keep the Phocians at bay while they were at war: If the Persians wanted to go through the pass at Thermopylae, they were going to have to climb a wall first!

The 300 Spartans were all hand picked by the King himself ... not because they were the best-of-the-best, but because Leonidas wanted soldiers who had sons, so no family would be altogether destroyed. These 300 Spartans, whose women themselves were bred to be able to say to those they best loved that they must come home from battle "with the shield or on it" -- either carrying it victoriously or borne upon it as a corpse -- were ultimately selected to sacrifice themselves for all of Greece.

A Persian Reconaissance Unit was sent to gather intelligence on the Hellenic Forces; however, they could not see over the wall which the Greeks were stationed behind. What they did see were the Spartans: Some playing sports and others, more strangely, combing their long hair. The "Recon" team rode back and told King Xerxes of what they had seen. The King had in his camp exiled Spartan Prince Demaratus as a counselor, and asked whether his fellow Spartans were insane to be employed instead of fleeing!? Demaratus' reply: "A hard fight was no doubt in preparation, and that it was the custom of the Spartans to array their hair with especial care when they were about to enter upon any great peril." (The Spartans braided their hair, since it served as an excellent defense against blows to the head when braided tightly.) Xerxes thought it all a joke, and waited four days for the Hellenic forces to withdraw. But the Spartans and the rest of the small force of 7,000 stayed to fight.

The night before the battle was to take place, a Persian consul under a banner of truce visited Leonidas and recommended that he surrender his forces. In Spartan fashion, Leonidas quickly refused. The consul continued: "Reconsider, as we will shoot so many arrows at you it will blot out the sun." Another Spartan, named Dienices, learning of the threat of this man-made eclipse, calmly replied: "So much the better. We shall fight in the shade." Leonidas knew there was only one currency which could purchase freedom for the Hellenic states, and it was going to be drops of blood from Hellenic soldiers.

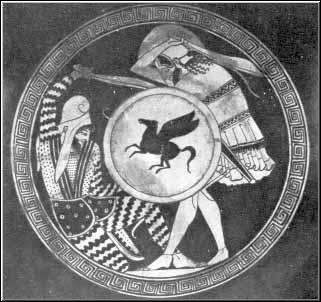

The Persians attacked, but were repulsed, it is said, three times; it is recorded that Xerxes leapt off his throne three times in despair at the sight of his troops being driven back. However, a Hellenic traitor named Ephialtes crept into the Persian camp and offered, for a large sum of money, to show a mountain pass that would enable the Persians to attack the Hellenic forces on two fronts. He was paid, and Xerxes sent a general named Hydarnes toward that alternative route. A small guard of Phocians was protecting this route, but they were quickly defeated by the mass of Persians. A few escaped and gave the alarming news to Leonidas. [Image: Hoplite killing a Persian, from a cup by the Triptolemos Painter.]

The Persians attacked, but were repulsed, it is said, three times; it is recorded that Xerxes leapt off his throne three times in despair at the sight of his troops being driven back. However, a Hellenic traitor named Ephialtes crept into the Persian camp and offered, for a large sum of money, to show a mountain pass that would enable the Persians to attack the Hellenic forces on two fronts. He was paid, and Xerxes sent a general named Hydarnes toward that alternative route. A small guard of Phocians was protecting this route, but they were quickly defeated by the mass of Persians. A few escaped and gave the alarming news to Leonidas. [Image: Hoplite killing a Persian, from a cup by the Triptolemos Painter.]

In the morning, after a short meeting of the war council, it was decided that Thermopylae was an undefendable outpost. Leonidas and his army of 7,000 were ordered back south to Athens before they were encircled and it became too late to leave; but, although it was even acceptable in the martial Spartan tradition to abandon a post that was undefendable, he refused. He ordered all of the allied forces under his command back south to Athens; he had decided this is where he and his Spartans would die. The allied forces complied, and all that was left was the obedient 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians who said they would fight to the end, and 400 Thebans. That night, it is recorded that Leonidas toasted to all of his troops during their last meal: "Tonight, we shall Sup with Pluto!" In other words, "this is our last meal before we feast with the Dead!"

As the first light from Sol Invictus began to shine down upon the fatigued Hellenic forces, Leonidas and his men prepared for war. With the pan-Hellenic forces of 7,000, Leonidas had stood on the defensive; however, his only desire now was to make as great a slaughter as possible, so as to inspire the enemy with dread of the Greek name.

Without fear, and without waiting to be attacked, he and his small force of 1,400 went on the offensive. The 300 Spartans butchered Persians by the droves; Thespians fought with vigor; the Thebans fought for their lives. Leonidas was one of the first to be cut down, and the battle for his corpse would leave two Persian princes, Xerxes' brothers, dead; the Spartans refused to allow their dead king to be displayed as some trophy piece.

It was obvious the Greeks were superior soldiers man for man, but the tremendous numbers of their enemy soon began to wear them down: their spears broke from excessive use, and their swords began to dull. Before their final collapse, the Spartans and Thespians made their way to a little hillock within the wall, and there they made their last stand; the courage displayed by the Thebans vanished, and they surrendered to the Persians. They were given quarter, but all were branded with the king's mark as untrustworthy deserters.

The Greek historian Herodotus in his History recorded the final moments of the battle:

... the small desperate band stood side by side on the hill still fighting to the last, some with swords, others with daggers, others even with their hands and teeth, till not one living man remained amongst them when the sun went down. There was only a mound of slain, bristled with arrows ... those with weapons still clutching them.Twenty thousand Persians had died before that small number of men!

After the battle, Xerxes asked Demaratus if there were many more at Sparta like the 300. He was told there were 8,000 more like them. Xerxes was not enthralled with this answer, and ordered more reinforcements.

Leonidas' body was cut up and displayed to deter the Greeks from resisting, but the warning did not work. The Spartans would clash shields again with the Persians many more times, and Persian defeat would eventually come when a Spartan named Aristodemus, who was evacuated at Thermopylae with the allied forces (he was deathly ill, but called a "coward" nonetheless by his fellow Spartan citizens) fought in the name of Leonidas and crushed the Persians one last time and drove them ingloriously from Greece.

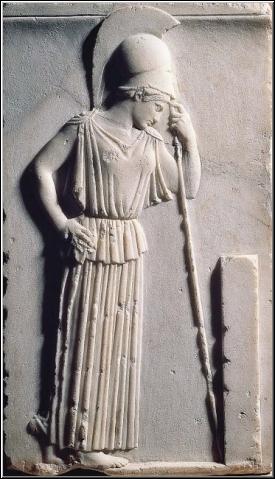

It is this Western spirit of determination that gave the 182 at the Alamo the courage to resist an overwhelming Mexican Army of 4,000, slaughtering 1,400 Mexicans before being taken. It is this battle hardness that allowed 105 British Soldiers to repel an attack of 4,000 Zulu warriors at Rorke's Drift, who after the battle were honored by the Zulus for resisting overwhelming odds. It is this innate legacy that gave the Totenkoph Division of the Waffen-SS -- bruised, battered, and battle fatigued -- the spirit which refused to surrender. They held their ground for 73 days against impossible odds in the Demyansk Pocket against a Red Army many times their number. And it is the same unwavering dedication that gave the 1st Marine Division in Korea the determination to duke it out with 10 Red Chinese divisions at Chosin; outmanned 10-1, they fought vigorously, finally making their way back to sea after breaking through an entrapment of insurmountable odds. Like those at the Alamo, Rorke's Drift, or the Waffen-SS at Demyansk, the United States Marine Corps stayed dedicated to their one commandment: Semper Fidelis! -- Always Faithful! [Image: Athena mourning a dead Greek hero; fifth-century marble relief in the Acropolis Museum.]

It is this Western spirit of determination that gave the 182 at the Alamo the courage to resist an overwhelming Mexican Army of 4,000, slaughtering 1,400 Mexicans before being taken. It is this battle hardness that allowed 105 British Soldiers to repel an attack of 4,000 Zulu warriors at Rorke's Drift, who after the battle were honored by the Zulus for resisting overwhelming odds. It is this innate legacy that gave the Totenkoph Division of the Waffen-SS -- bruised, battered, and battle fatigued -- the spirit which refused to surrender. They held their ground for 73 days against impossible odds in the Demyansk Pocket against a Red Army many times their number. And it is the same unwavering dedication that gave the 1st Marine Division in Korea the determination to duke it out with 10 Red Chinese divisions at Chosin; outmanned 10-1, they fought vigorously, finally making their way back to sea after breaking through an entrapment of insurmountable odds. Like those at the Alamo, Rorke's Drift, or the Waffen-SS at Demyansk, the United States Marine Corps stayed dedicated to their one commandment: Semper Fidelis! -- Always Faithful! [Image: Athena mourning a dead Greek hero; fifth-century marble relief in the Acropolis Museum.]

Today, however, Western man's life is out of balance. The unwritten codes of honor, values thousands of years old, seem to be no more: the courageousness of his spirit has been siphoned to near extinction from his soul. On the modern battlefield, too many fail to speak up because they are afraid of the PC Hit Squad calling them "fascist," "racist," or "neo-Nazi." Of the great feats recorded in our history, our most disgraceful is not defeat by the hands of the enemy, but in modern times our servile acceptance of such words, which have become a wall that we must surmount to regain our cultural sanity. Such cowardliness was not a trait of our ancestors, and although many of us call ourselves descendants of these heroes, I will continue to doubt it until I see legions upon legions of Euros marching to defend the West.

Like those at Thermopylae, there remain a few who remain faithful to accomplishment; however, like the 300 Spartans, and the 700 Thespians who fought to the death, does the fight for the West die with them?

In 191 BC, the Roman forces at Thermopylae routed Antiochus III, repeating the maneuver executed by Xerxes in 480 BC, and forever keeping the Persians out of Europe. With the threat of the barbarian once again at the gates of the West, is there anyone to stop them? This remains to be seen.

PRO MAGNA EUROPA, VIVE ET MORI!

![]()

Honor to those who in their lives

have defined and guard their Thermopylae.

Constantine P. Cavafy, Thermopylae (1903)

No comments:

Post a Comment